Taking in Chris and Kim Nietch’s Columbia Tusculum home, you’d never guess that the red metal roof is anything more than a chipper nod to history, or that the woven flooring in Kim’s lower-level yoga studio is more than an aesthetic consideration. But these purposeful selections, made during a renovation that began about three years ago, foster a connection to the environment in more ways than one.

“It’s a ‘walk the walk’ sort of thing,” Kim explains.

The yin/yang balance of nature is a core concept for both Chris and Kim, who moved to Cincinnati from New Jersey in 2006. While Kim helps yoga students steady their body and mind, Chris works as an environmental scientist for the Environmental Protection Agency. So when they realized their plans to expand the 1890 Steamboat Gothic-style home would increase the square footage by a third, they worked with architect Tom Warner and contractor Tony Beck to practice what they preach—using renewable energy to offset the additional resource consumption.

Two solar thermal panels—installed on the roof of a rear dormer—are the heart of a system that is designed to heat domestic hot water as well as radiant flooring for the yoga studio.

While open windows and ceiling fans are often enough to beat the heat come summer, sometimes nature needs a little help. Using wall-mounted zonal units in the studio, lower-level bath and third-floor master suite, a super-efficient ductless heat pump system extracts heat from the indoor air and releases it outdoors.

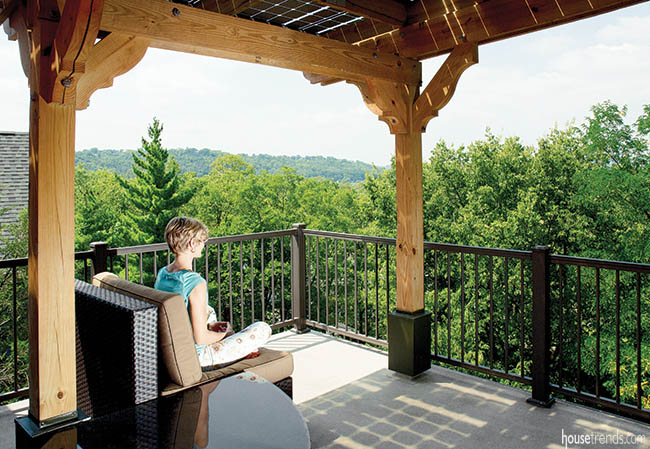

Because the home is located in the Columbia Tusculum Historic District and the City of Cincinnati, these eco-friendly amendments had to respect some man-made environmental needs. Although the front roof is in perfect position to capture solar energy, photovoltaic panels would have disturbed the historic character of the facade, which is protected in the district. As a creative alternative, the couple used a new breed of panels to create a shady third-story pergola at the back of the house, overlooking the garden.

With frameless modules and a clear back sheet, the panels resemble modern design elements while providing about one-third of the home’s electricity—essentially negating the additional energy consumed by the home’s expansion, Kim says.

Guidelines from the community’s historic board also dictated the selection of HardiePlank fiber cement siding, which replaced the home’s rotting cedar planks and poorly installed aluminum siding.

And while the red metal roof retains historic accuracy, it has yet to embrace its larger purpose: supplying a constant source of rainwater for use in toilets, laundry, and irrigation. Although the components are in place, the Nietches will need a permit from the city before engaging the system that has to meet the water quality and sewer metering requirements of a relatively new and restrictive rain harvesting ordinance.

Inside, the couple used reclaimed and sustainable materials to enhance the home’s character without increasing its environmental footprint.

On the main floor, sagging floor joists from the kitchen were salvaged and used to frame steel beams that once supported a three-story deck—creating weighty columns with a historic feel. And although a thin, built-in hutch on the staircase appears original to the home, it was created using disconnected double doors found during the renovation.

Throughout the home, finishes made from recycled materials lend a natural yet modern vibe. Caesarstone kitchen countertops that never require sealing consist of crushed quartz—a by-product of mining operations, and the sinks are made of recycled cast iron.

In the yoga studio, long-lasting Chilewich floor covering has the zen-like look of natural woven fibers, but also provides a permeable surface for the radiant heat flooring and incorporates cushioning made from post-consumer recycled material.

Outside, Kim’s stepping-stone “meditation path” wraps around the home and alongside a recirculating pond and stream.

This feature was designed and built by Chris, who conducts research in the field of water quality management and stream ecology, and is integrated with the design of the rain harvest system.

“It’s just a water feature, but means a little more,” Kim says.